As humanity’s population grows exponentially, so does our environmental impact, and there is a need to accommodate such a large global population. Human-wildlife conflicts are expected to increase dramatically, as will human encroachment on wildlife habitats. The negative impacts of human-wildlife conflicts with tigers can vary, from lethal encounters, threats, and killing of livestock; these can obviously foster negative attitudes towards an endangered species. Negative attitudes towards tigers can lead to retaliatory killings of tigers, habitat destruction, and non-compliance with wildlife regulations. As a result, this can contribute to the tiger population’s decline and hinder conservation efforts. This study aimed to evaluate the attitudes of locals in the direct proximity of Chitwan National Park in Nepal to prioritize targeted conservation strategies. This research is important not only within the regional context of Nepal but also in providing insight/strategies for human-tiger coexistence in other areas of the world.

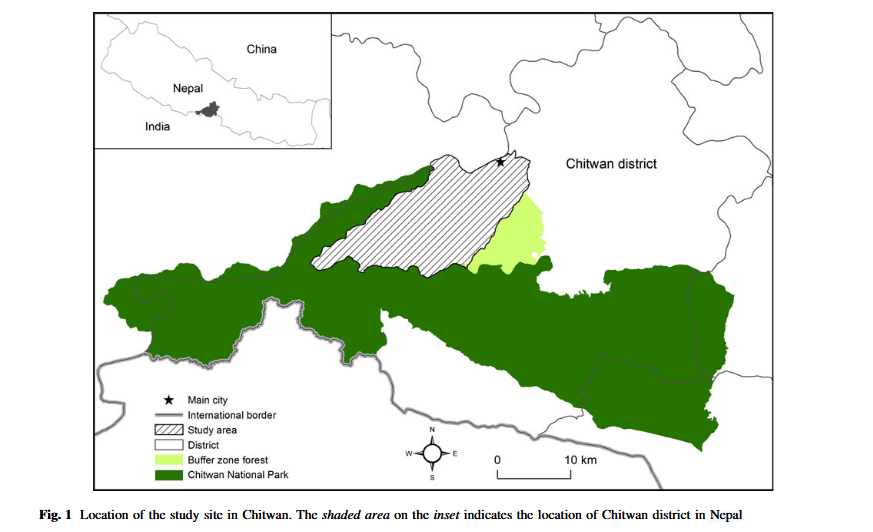

Chitwan National Park is a large forest (~1000km^2) that provides critical habitat for the endangered tiger (Panthera tigris). The national park’s buffer zone is a part of Nepal’s community forestry, allowing locals to harvest resources sustainably, such as; firewood, medicinal plants, and grazing area. It is also important for the livelihood of the locals, supporting an ecotourism industry and subsistence grazing/agriculture. The study site of the article is the westernmost part of the Chitwan district in Nepal, which borders the national park; it was broken down into “wards” (small administrative units used by Nepal), and the wards that were in the immediate vicinity of the national park where surveyed.

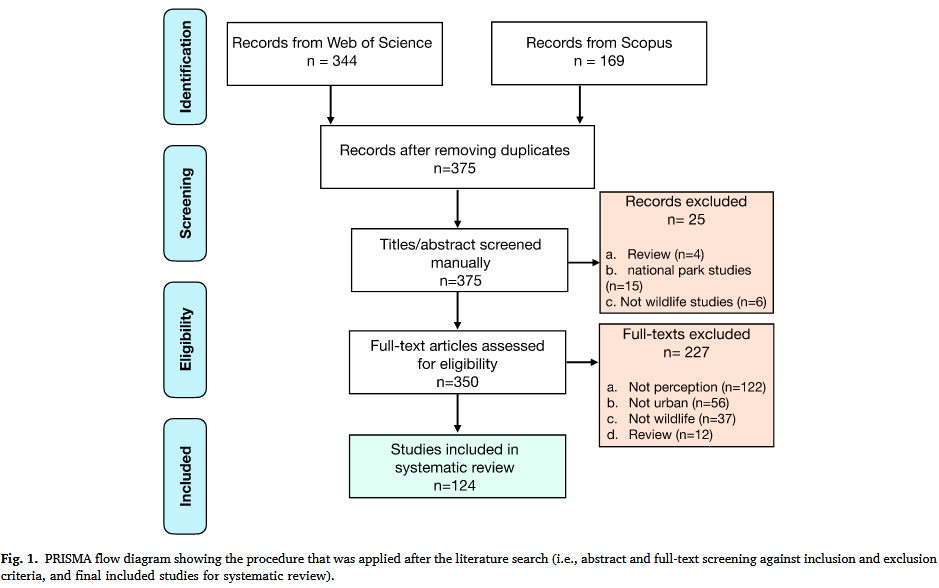

A stratified sample was made through the wards, where 500 individuals were randomly selected to participate in the attitudes survey. The attitudes survey included demographic information (age, gender, and ethnicity/caste) and socioeconomic information (education level, occupation, and how many livestock their household owned). It also included their tiger-related risks, such as how long they had lived in Chitwan, how often they went into the forest, and negative experiences with tigers.

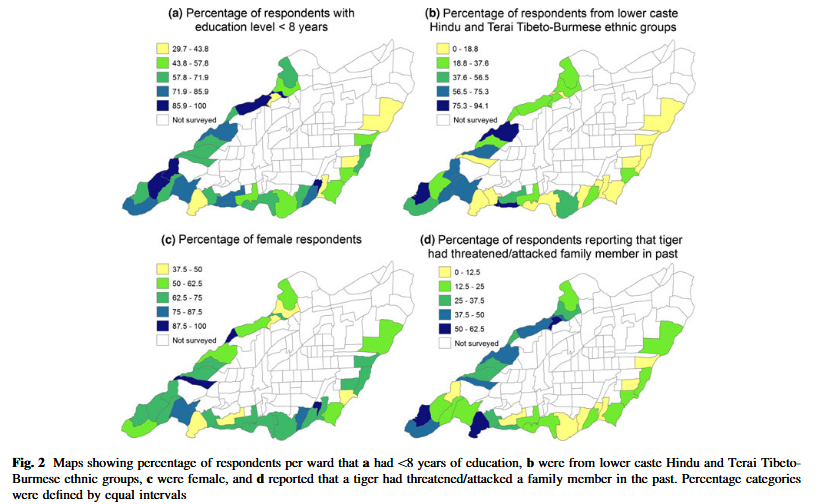

The study results showed that one’s position in society shaped their attitudes more than having direct negative experiences with tigers. The researchers hypothesized that this is due to the fact that those of higher castes are more likely to be involved in the ecotourism industry, seeing the direct monetary value of tigers, instead of lower castes who are more likely to be subsidence farmers/rely on the forest products of the Chitwan national forest. Those with greater education also show more positive attitudes towards tigers, possibly because it broadens their perspective of tiger conservation and their ecological value. Those in lower castes/marginalized ethnic groups showed greater negative attitudes due to the reliance on forest products, where the presence of tigers is threatening, and how the conservation of the national forest restricts access to forest products that their livelihoods depend upon. Women also tended to have greater negative attitudes towards tigers, as they were primarily responsible for agricultural tasks/resource gathering, constraining their perception of tigers to tangible negative consequences.

There is an obvious spatial relationship between previously discussed trends, education, gender, ethnicity, and tiger exposure. Digging into this research article has expanded my perspective on the complex relationships between social structure and economics and how an individual’s experience affects wildlife conservation. Attitudes are not solely dependent on one’s experience with tigers but are deeply embedded within the context of the social/economic system one lives in. This study highlights the importance of targeting conservation strategies to various social groups within their own needs and experiences.

Carter, Neil H., et al. “Spatial Assessment of Attitudes Toward Tigers in Nepal.” AMBIO, vol. 43, no. 2, Mar. 2014, pp. 125–37. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-013-0421-7.