Black bears are very intelligent animals. Unfortunately due to urbanization, this can become a problem. It is common for black bears to find their way into trashcans or other sources of anthropogenic food. Walking down a neighborhood and knocking over trashcans is a lot less effort compared to wandering around the woods. This results in a variety of issues. Harm to property, individuals, and the bear itself are the major issues.

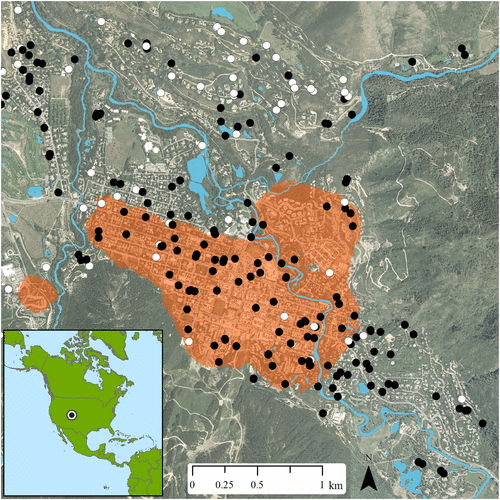

This study was conducted in Aspen, Colorad between the years of 2007 and 2010. It is associated with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, USDA National Wildlife Research Center, and other natural resource related departments. This research is essential based on selection within an urban landscape. Would a bear, in an urban area, eat antropogenic food or naturally forage? This paper defines resource selection as disproportionate use of a resource in comparison to its availability. The topic of black bears specific selection patterns in urban environments.

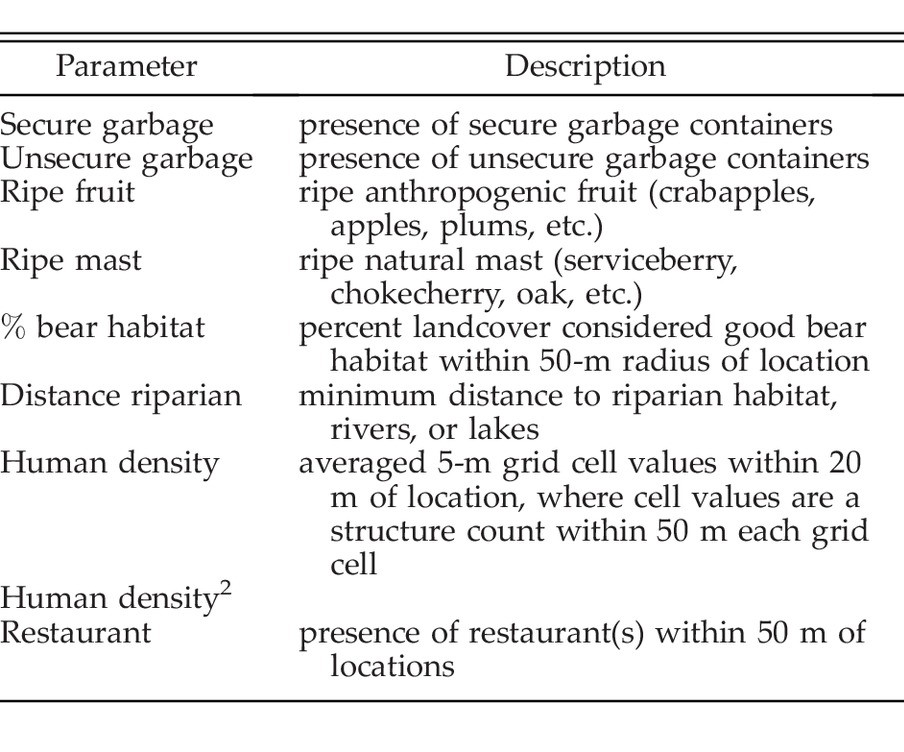

This study utilized GPS radio collars. 40 in total bears were captured with no specific method mentioned. Number of bears varied through year, but remained similar. They were fitted with GPS remote-downloadble radio collars. These collars would send locations every 30 minutes. The researchers then monitored the bears location during May-Septemeber for 4 years. They would also backtrack to bear locations, with a specific set of methodologies. These methods involved using a randomized list of locations, not backtracking recent locations to avoid disturbing the bears, and only backtracking locations within 50m of building structures. The last point was because foraging behavior beyond this distance was not frequent in Aspen. 42,599 locations were gathering that followed that specific last rule. 2,467 of those locations were backtracked from 24 bears. Once at the location, they would search a 20m radius in search of anthropogenic food sources. They would also acknowledge natural foraging evidence.

The researches acknowledged that foraging specifically regarding anthropogenic food source foraging could be opportunistic. Because of this, they expected a higher level around areas such as travel corridors and bear habitat.

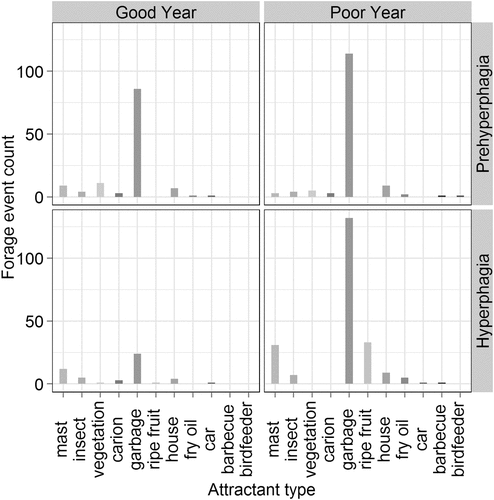

In total, they classified 122 natural foraging events, 397 anthropogenic foraging events, and 12 combined events. Specific amount of bears becomes a bit confusing here. They list that year 2007 had 11 bears, 2008 had 6, 2009 had 10, and 2010 had 4. This totals to 31, which differs from the original 40 number of bears stated previously. It is possible that 9 of the bears that were collared did not forage within the range after collared. Bears involved with less foraging events lost their collars prematurely, were dispersing males, were removed due to human conflict, or occured in a year with good natural food production.

This graph indicates the foraging events and what food source was associated with them. Garbage shows a high use, even in the good years. Prehyperphagia, the top portion, is associated with the early part of the season (May and July). Hyperphagia is associated with fall (August-September). This graph has a very specific set of attractant types. Car, house, and barbeque indicate that the bear tried to break into those areas for food. Fry oil is not mentioned within the paper, but it can be assumed that it is more associated with restaurant waste.

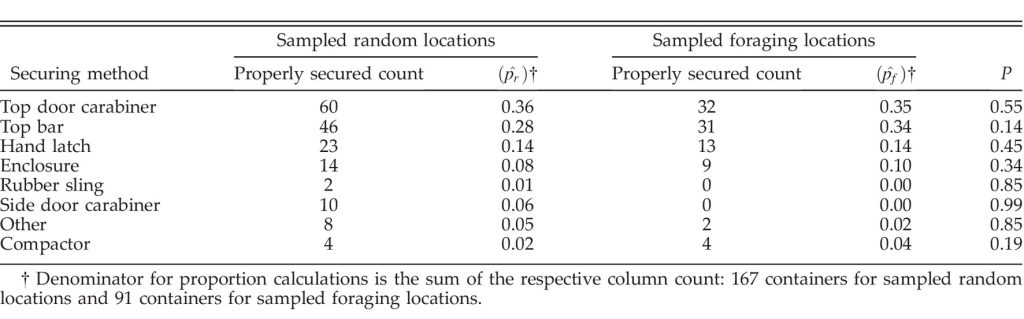

A sort of sub-experiment was conducted involved garbage storage devices. 384 garbage containers at random locations were selected. 76% were bear-resistant, but only 57% of those were properly used.

This paper’s findings can be utilized in the future. It showed a clear selection of garbage by black bears. This information could be used to persuade governments or companies to require properly used bear-resistant trashcans. Promoting natural forage material would also be beneficial. Avoiding construction near travel corridors or bear habitat would also discourage anthropogenic foraging.

The basis of this paper is well done. A few portions of the paper lack information. More information on specific details of trapping the bears, information by year-by-year information, and specific categories of attractant types would benefit this paper. I think the methods are good. Other possible methods could have included camera trapping buildings over radio collars. Cameras that are active when movement is sensed might have been a bit cheaper. Radio collars for large mammals can cost around $3,000 while trail cameras cost around $50. This would come with the lack of specific identification, so if specific detail was wanted the radio collars would be better. It seems this study was specifically focused on amount of interactions, so cameras might have been better.

Lewis, D., Baruch-Mordo, S., Wilson, K., Breck, S., Maso, J., & Broderick, J. (2015). Foraging ecology of black bears in urban environments: guidance for human-bear conflict mitigation. Ecosphere, 6(8), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES15-00137.1