The human population in urban areas will increase by 2.7 billion from 2010 to 2050. Vertebrates such as amphibians are under threat, about 40% of amphibian species are threatened with extinction. Urban development affects around 950 amphibian species with extinction. This paper stresses the concerns about how amphibians are some of the least studied vertebrate groups in urbanized landscapes, and how most land management is derived from studies of a few common species mostly leaving out amphibians and in turn failing to cater to all affected species leading to a higher risk of decline.

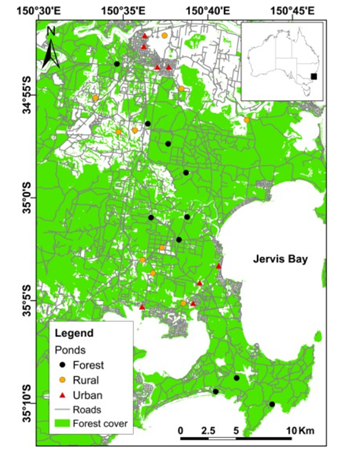

The researchers studied the distribution of pond-breeding frogs during breeding season in an area consisting of rural, forests, and urban areas. The site was focused in southeastern Australia, specifically it was conducted between Nowra and Booderee National Park.

The area is mostly dominant with native eucalypt forests and wetlands, consisting of both urban and rural areas. The researchers surveyed a total of 28 ponds within the study area boundaries. Frog calls were recorded at ponds during breeding season as this is when peak calling activity occurs. The researchers did state that two sites were not surveyed in urban areas due to vandalism and access, which I thought interesting as this could skew the data, especially since we are specifically looking at urbanization effects.

Aquatic and terrestrial variables were measured, variables such as water body size, and cover of surface vegetation. For this study they also took into account an exotic fish species, the eastern gambusia, because of its negative impact on frog populations. Personally, I feel this is an important factor to consider when studying specific species. This framework could be implemented when studying other species, it would obviously vary based on location. I believe the measurement of the exotic fish factor to be short. The researchers performed one five-minute visual search and placed a trap in the pond for three days. I don’t believe that to be maximizing efficiency on that specific factor, but data was captured, nonetheless.

It was found that some frog species had a positive association to urbanization while others had a negative association. It is known that the number of roads has a negative correlation to frog species richness. The paper suggests biodiversity metrics such as total species richness may underestimate urbanization impacts. It is still suggested that urbanization is a key driver in loss of pond-breeding frogs in the study region. Only one breeding season was examined in this study, yet the researchers expect the patterns of occurrence to be common to what was quantified and reflected in this study. Ultimately it was concluded that uncommon frog species are more sensitive to terrestrial modification where common frogs respond more to local aquatic variables.

I felt this paper was great at identifying the environmental variables that correlated to uncommon and common frogs. I did feel the paper lacked the measurement of environmental conditions. An example would be humidity and soil moisture. I feel the study could have been constructed in the manner of grouping the different study sites based on these factors rather than consolidating them to a basic body of water label. Also, the sites were based on urban, rural, and forested areas, the lack of knowledge on the history of the urban study sites I feel affected the data presented. The reader does not know if the urban areas are settled, or newly constructed. I feel knowing if the frogs have adapted to the changed environment or are adapting is crucial to scaling the impact of urbanization.

Villasenor, Nelida R., and Don A. Driscoll. “The Relative Importance of Aquatic and Terrestrial Variables for Frogs in an Urbanizing Landscape: Key Insights for Sustainable Urban Development.” Landscape and Urban Planning, vol. 157, Jan. 2017, p. 26–35, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.06.006.